The Dream That Had Fins, Page 7

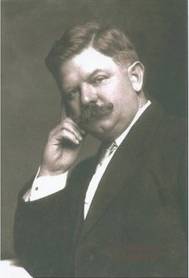

A gentle man, with an almost child-like simplicity of manner, Simon Lake was more creative genius than businessman. He often didn't bother to patent his inventions (his work with periscopes, for example), and other inventors capitalized on his ideas. In other instances he let his patents expire and lost millions in royalties. In his autobiography, Simon Lake explained his laxity in money matters: "My interests have been more in doing things than in making money . . . I would rather die broke because I had been spending my life doing worthwhile things in-stead of sitting around cutting coupons." The bane of his life were "skrimshankers and- belly-achers."

During his European ventures, the lingering romance of his boyhood, treasure hunting in a submarine, again welled to the forefront of Simon Lake's consciousness. He be-came intrigued with the fate of the Lutine, a French frigate which hit a reef and sank in the Zuider Zee in 1799 with a fortune in gold bullion aboard. Lloyd's of London, which had insured the shipment; maintained proprietory salvage rights.

Simon Lake contracted with Lloyd's to personally pay all costs -of the salvage operation in return for 50% of the recoveries from the Lutine for a period of two years. He built a diving bell and a steel salvage tube, similar in design to the one which he would one day discard in Milford Harbor.

Lake never used that equipment. He had another faint glimmer of hope that his own country might be interested in his submarines; so he stored his salvage apparatus at Brightlingsea on the English Channel in 1908 and returned to his beautiful mansion-like home on the green in Milford.

The Lake Torpedo Boat Company* in Bridgeport was going full blast, building submarines for foreign governments, but the inventor turned all of his private capital and his inventive genius into the construction of the Seal, a super-sub which he offered to the navy with the stipulation that "if it does not do all that is claimed for it, the government need never er pay me one cent."

The Seal, renamed the USS-GI, did all that was claimed — and more. It was commissioned on October 28, 1912, and set a world record by sub-merging to a depth of 256 feet. That same year the U.S. Government formally adopted the Lake-type submarine and many were built throughout World War I, not only in Bridgeport, but in U.S. Navy yards under royalty to the Lake company.

Submarine construction came to a virtual standstill when World War I ended, and in 1922, when the Lake Torpedo Boat Company was straining to keep its 5000 workers employed, Simon Lake embarked upon a superb one-man public relations effort which would make any Madison Avenue campaign appear amateurish. He set out, single-handed, to alter the unpalatable reputation of sub-marines as silent, mysterious killers. He wanted to reverse his own government's opinion that the war-to-end-all-wars necessitated relegating the submarine to a mothball existence. He tried to transfer, by verbal osmosis, to anyone who would listen or read, his prophetic boyhood vision of submersibles as scientific under-water laboratories, as cargo carriers, as salvage vehicles, and even as art studios where sea life could be filmed.

In less than a year, and at his own expense, Simon Lake wrote volumes on the peacetime uses of submarines for magazines, scientific journals, and newspapers. He bought full-page ads in the country's leading dailies. He lectured at universities, at science conclaves, and to the man-on-the-street. He knocked on thousands of doors in neighborhood canvasses. He was a frequent visitor to Washington, hoping to impress government officials with the practicality of converting old submarines to peacetime uses.

He pleaded. He begged. He cajoled. But few would believe that submarines, which had sunk more treasures than they had ever raised, could ever square the accounts. And Lake's boat company in Bridgeport finally folded in 1923.

Among the more spectacular Lake endeavors in the '20s and '30s were a plan of treatment by vacuum which was very similar in basics to an iron lung; the development of a prefabricated house; the restructuring of a 1917 submarine, the 0-12, for use by Sir Hubert Wilkins in his historic under-ice Arctic attempt; the building of the Baby Explorer, a 22-foot-long midget sub which Lake used, himself, for seafood farming and oceanographic study in Long Island Sound; and, in 1937, the completion of his diving chamber (named Argonaut III) and the salvage tube.

Simon Lake was 71 years old, but he set out in search of the Hussar as enthusiastically as a teenager. With him went a crystal-clear boy-hood vision, a scientist's sober intent, a limited amount of capital, and a small crew of expert divers.

That the Hussar did, indeed, sink when it hit Pot Rock in Hell Gate is well documented, and a claim was made, but never verified, that her anchor had been recovered in 1823. Lake spent that entire summer and part of the fall on his long anticipated treasure hunt. Confident of success, he even announced that his second salvage target would be the Lusitania if the British government would renew a contract he had held with them until December 31, 1935.

He also fully intended, before he died, to take a submarine trip with his good friend, famed naturalist Dr. William Beebe, in search of the lost